Dear Constant Reader,

As part of the mentorship program with The House of Knyle, we each had to write an essay on a Legend. I think most of the other women chose living Legends — I know some of the subjects were Shawna The Black Venus, Miss Topsy, and Kitten DeVille. Because I like a good challenge, I chose Sally Keith, a performer strongly associated with Boston and Scollay Square. She was very well-known, but as it turns out, not known well. I had to do a lot of digging to get beyond a couple of superficial stories and along the way I found a lot of contradictions. perhaps in my spare time (“spare time”, I’m so funny!), I’ll continue my research.

[Note: I made a couple of corrections for grammar and spelling that I missed when I originally submitted this and added one tidbit that surfaced after the due date.]

Sally Keith

Sally Keith

Queen of the Tassels

Sally Keith is one of the burlesque performers tied strongly to Boston during the Golden Age of burlesque in Scollay Square. For someone so famous, there is very little information on her personal life, especially before and after she performed in Boston. I’ve gleaned as much as I could about her life and career from newspaper articles, books, and some from people who knew her. The two main sources were her niece, Susan Weiss, and her protégé, Lilian Kiernan Brown (Lily Ann Rose), who wrote a memoir of her own time in burlesque. Memory is, of course, inherently unreliable, especially after decades, and and research is made even harder by the fact that Sally seems to have fabricated some of her public story, especially her age. This is her story, as best as I have pieced together.

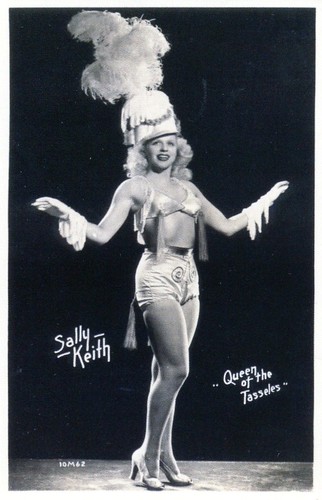

Known as “Queen of the Tassels”, Sally Keith performed at The Crawford House’s Theatrical Bar in Boston’s Scollay Square for almost 20 years. Her specialty was to twirl tassels on her breasts and buttocks. She was famed for being able to twirl in every direction, especially opposite. Her tassels were very long, I’d guess about 8 inches, and all the photos show them sewn to her costumes. I wish we could see her act, but it doesn’t seem to have been filmed. It was clearly memorable, since many people in Boston talked about seeing her, even decades later.

Stella Katz was born in 1913, in Cicero, Illinois, near Chicago. She came from a large Jewish family with eight brothers. Her father was frequently reported to be a Chicago policeman, perhaps because it made for better publicity. In reality he was a house painter, although Sally also said he owned a bakery. A beautiful blonde with lovely blue eyes, she changed her name to the less Jewish-sounding “Sally Keith” when she began performing in Chicago. “Keith” may have been an aspirational name, from the very prestigious B.F. Keith vaudeville circuit, onto which many performers dreamed of being booked. Unfortunately I haven’t found any information about where she performed in Chicago and if she was doing tassel twirling then.

She told Lilian Brown that she won a beauty contest at the 1933 World’s Fair (where Sally Rand got her start) at age 15. You may have noticed that the math doesn’t work — she seemed to be in the habit of shaving a few years off her age all her life. She was then discovered by a Jack Parr, who became her agent and taught her the tassel dance. He got her started in Atlantic City and then brought her to the Crawford House in Boston. Another source said it was Harry Richman, a popular entertainer of the time, who spotted her at a beauty contest in a Chicago suburb and he got her started on Broadway. I’m not sure how much, if any, of these stories are true. Her obituary in the Boston Globe states she was discovered at Leon & Eddie’s, a popular burlesque venue in New York, by Boston theatrical agent Ben Ford in 1937.

Ann Corio said “Sally Keith, next to Carrie Finnell, was the best tassel-twirler I ever saw. She didn’t have Carrie’s huge bosoms and fantastic muscular control, but she could make those tassels spin with a fury.” Carrie Finnell twirled her tassels using her pectoral muscles, which indicates that Sally didn’t. Sally’s secret to her amazing twirling, it’s said, was to weight her tassels with buckshot. In an interview she mentions painting her tassels with radium, so she must have done a twirling act that glowed in the dark. I’ve seen advertisements for her “electrified tassel dance”, which was probably the one.

Scollay Square, a restaurant in Boston, claims to have a pair of her tassels, but I don’t think they’re authentic because they are attached to pasties. According to reports and photographs she wore the tassels attached to her costume, rather than to her body. Her twirling costumes are fairly modest, at least by modern standards. I don’t think she stripped during the tassel dance, but she did in other parts of her act. An MIT student remembers going to her dressing room to ask for a g-string as part of his fraternity initiation. She invited him and his brothers to see the show, saying she was tired of Harvard men.

Besides twirling her tassels and dancing, Sally also sang. Some of her singing captured on 78 records in the 1940s, which I think they were just live recordings of her shows. She also composed at least one song, “Belittling Me”, which was published as sheet music. Her photo, in her tassel outfit, graces the cover.

Her home base, the Crawford House, was a hotel and restaurant which opened in 1867 and lasted until it was demolished in 1962, like the rest of Scollay Square, to make way for the new City Hall and Government Center. A few sources say Sally eventually owned the Crawford House, but I haven’t found any evidence of that. She was so strongly associated with it and may have had some creative control over the shows that people may have just believed she was the owner as well.

At the Crawford House, Sally reigned at the Theatrical Bar. It began as The Strand Theatre, a 24-hour movie theatre under the Crawford House, but been transformed by the early 1930s. Patrons could see “3 Sparkling Floor Shows Nightly”, featuring comedians, dancers, and of course Sally Keith. Her photograph was even on the cover of the restaurant menu.

During the War, Sally did her part for the troops, touring with the USO and visiting military bases. She was even named “Sweetheart of Camp Edwards”. Some of her support for the troops may have been because most of her brothers were serving. She liked to live large, with furs, jewels, and elaborate clothes, but she was also generous with her money. She put aside part of her earnings for war bonds. A newspaper article praised her incredible generosity and listed some of her good deeds, like paying for medical treatments and tuition for the less fortunate. According to the article, one of the beneficiaries of her largess had willed her his life savings of $18,000. This may have just been a publicity stunt, but she did perform in benefits to help others. She was certainly very generous with her family, sending money home to support them. Her niece recalls that when her parents went to Boston for their honeymoon, Sally picked up the tab.

She owned a gold Cadillac convertible with leopard-covered seats and monogrammed doors. The color went beautifully with her platinum hair, but she was a terrible driver. She knew it and would have other people drive her around, like her 14-year-old protégé, Lily Ann Rose (Lilian Keirnan Brown). Sally didn’t seem to care that Lily Ann didn’t have a driver’s license – she was much better behind the wheel than Sally.

Another of Lily Ann’s jobs was getting Sally in and out of bed when she’d had too much to drink, apparently a fairly frequent occurrence. Although the Crawford House served a cocktail in her honor, The Tassel Tosser (brandy, anisette, and Triple Sec — for just $1), Sally preferred stingers, a mix of brandy and crème de menthe. Her drinking problem seems to have continued her entire life.

1948 was a big year for Sally, making headlines in the local papers. On January 5th, Sally had finished her last performance of the evening and had gone up to her suite in the Crawford House hotel. She answered a knock at her door, thinking it was the bellboy, bringing her a sandwich. Two men burst in and knocked her down. She struggled and one of them tore off her clothing while the other grabbed her $4000 mink coat and $600 worth of costume jewelry, leaving about $35,000 of real jewels behind. The coat was later recovered in the hotel. Sally made the front page of a Boston paper with a photograph showing the bruises she had sustained in the attack. She moved out of the Crawford House shortly thereafter.

Sally’s niece, Susan Weiss, claims the whole thing was a publicity stunt and the bruises were just makeup. Lily Ann Rose says the robbery actually happened and Sally kept her jewelry in a bank after that, except for two diamond necklaces that Sally and Lily Ann wore all the time for safe keeping.

In March of the same year there was a fire at the Crawford House. Sally had moved out by then, but her wardrobe was still kept in her suite. She burst into the building demanding to go to her rooms where she had $100,000 worth of furs, jewelry, and costumes. The Boston Herald reported “Sally Keith Grinds Her Way into Blaze, Bumps Fireman”. The fire destroyed two stories of the hotel, but not Sally’s rooms on the second floor.

Like many of her contemporaries, Sally modeled for girlie magazines and ended up on a couple of covers. I haven’t found any evidence that any of her performances were filmed. It’s too bad that her act wasn’t preserved because her tassel dance sounds like nothing anyone else was doing. Sally was noted for not taking herself too seriously as a performer, but her career lasted for decades. She was clearly a decent businesswoman as, unlike other burlesque performers of the era, she seems to have managed her finances well.

I found mention of her performing in Boston as late as 1960. Although she is strongly associated with Boston and The Crawford House, she performed in other venues and cities, like New York and Miami. She also performed internationally, with tours of Europe and South America. In the late 1940s The Sally Keith Revue, created by and starring Sally Keith, of course, opened in Boston for three months, then went on to New York City for several months. For the summer the show moved to Lake Geneva in upstate New York.

There’s very little about Sally’s personal life. We know she married twice. Her first husband was her agent, Jack Parr, who she divorced when she was 22 because he was too controlling. If she had any romantic relationships while she was in Boston, they were kept very quiet. She married her second husband, Arthur Brandt, after she had retired from performing and was living in Hollywood, Florida. She had no children.

She died on January 14, 1967 in New York of cirrhosis of the liver or perhaps a cerebral hemorrhage – sources differ. Besides her obituary in the Boston Globe, I found a tiny squib in a newspaper in Lowell, Massachusetts mentioning her upcoming funeral. Both that notice and a reminiscence by a Globe reporter listed her age as 51. Keeping with her lifelong practice of taking a few years off, she was actually a few years older. Ed McMahon, who performed at the Crawford House, mourned her on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Sally Keith may have been indelibly linked to Boston, but she deserves to be known more widely. Her tassel dance sounds like something unlike any other tassel twirling act, past or present. She should be included in any list of tassel-twirling legends, alongside Carrie Finnell, Satan’s Angel, and Tura Satana. I hope more present-day burlesque performers take inspiration from her.

Bibliography

Brown, Lillian Kiernan. Banned in Boston: Memoirs of a Stripper. 1st Books, 2003.

Corio, Ann., with Joseph DiMona This Was Burlesque. Madison Square Press, 1968.

Kruh, David. Scollay Square. Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

Kruh, David. Always Something Doing: Boston’s Infamous Scollay Square. Northeastern University Press, 1999.

Kruh, David. “Sally Keith, Queen of the Tassels.” Welcome to Scollay Square.

Zemeckis, Leslie. Behind the Burly Q: The Story of Burlesque in America. Skyhorse Publishing, 2013.

“Scollay Square and Tales from The Crawford House.” New England Historical Society.

“Sally Keith Beaten, Robbed.” Boston American, 6 Jan. 1948.

“Sally Keith Grinds Her Way into Blaze, Bumps Fireman.” Boston Herald, 24 March 1948

“Sally Keith’s Unknown Friend.” The American Weekly, n.d. 1948.

“Sally Keith Dies in New York, Long a Hub Entertainer.” Boston Globe, 15 Jan. 1967.

“Sally Keith Rites Wednesday.” Lowell Sun, 16 Jan. 1967.

These writings and other creative projects are supported by my Patrons. Thank you so much! To become a Patron, go to my Patreon page.

These writings and other creative projects are supported by my Patrons. Thank you so much! To become a Patron, go to my Patreon page.